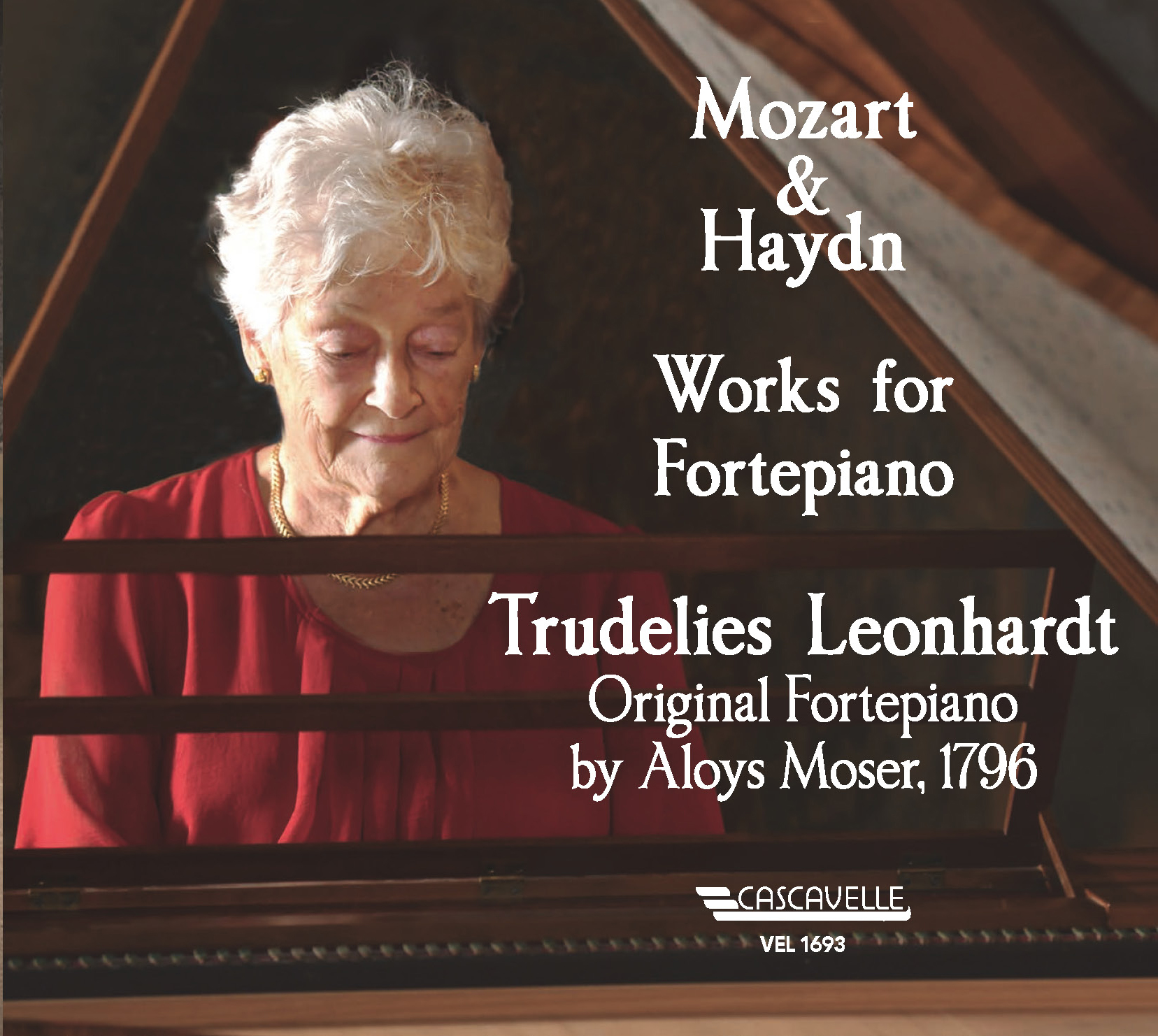

Trudelies Leonhardt

“Rarely have we heard such vibrant and compelling playing as hers…” Pizzicato, Luxembourg

Biography

“It was a great privilege to be born into a family that so loved music: my path in life was laid out…”

My Austrian mother was an excellent violinist, and my Dutch father a flautist – though neither of them played professionally, both were deeply attuned to music. They were surrounded by musician friends and great artists, whom my parents had the excellent idea to invite to our house whenever they were on tour in the Netherlands. That’s how Trio Pasquier, baritone Gérard Souzay, the Hungarian Quartet, Antonio Janigro and so many others came to stay with us, thrilling the admirative mini-pianist that I was at the time. I religiously absorbed every bit of advice they gave me. Swiss pianist Adrian Aeschbacher was very close to the family and was a great example to me. He always stayed with us if he was playing concerts in Holland and each time found a moment to teach me.

This was the music-filled atmosphere that my brothers and I were lucky enough to grow up in. Our first piano teacher was Johannes Röntgen, composer Julius Röntgen’s son. He taught all three of us. Everything about him was music… even when he talked, he’d be singing! And he spread such musical joy! My older brother was an oboist, but chose to be an engineer in life. The next brother down, Gustav, became a world-renowned harpsichordist – the ‘king’ of harpsichord and baroque music… that’s him!

As for me, after my obligatory schooling, I studied the theory of music with Anthon van der Horst and was accepted into the Conservatorium van Amsterdam under the eminent pianist Nelly Wagenaar. I graduated with a diploma cum laude in concert performance and then, after receiving the Elisabeth Everts Prize, I continued my studies in Paris with Yves Nat and Marguerite Long.

I’ve had the great honour and pleasure of performing as guest soloist with orchestras such as the Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Eugen Jochum, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich led by Jean Meylan, the Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne under Victor Desarzens, and the London Mozart Players directed by Harry Blech.

My brother Gustav once said, “Musical works should be played on instruments of their time!” This piece of advice radically changed the beginning of my career. It sent me searching for and eventually buying a fortepiano (initially a Carl Andreas Stein, then a Benignus Seidner from around 1815), and researching into the lives and times of my favourite composers, Beethoven and Schubert. For Mozart, it needed to be an older instrument, which I found in the form of an Anton Walter copy made by today’s great fortepiano builder Paul McNulty.

For the past 40 years I’ve concentrated my interests and musical activities on late 18th and early 19th century repertoires, to my greatest satisfaction and enjoyment. Working with Michel Amsler and Studio MediaTone, I have respectfully tried to express this passion – infused with joy… and love – on more than 30 CDs released under a number of European and American labels.

Discography

Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Field, Mendelssohn, Schumann and v. d. Horst. In all gratitude for their beautiful works…

In the press

Trudelies Leonhardt has made a simply astounding contribution to recordings of Schubert’s piano concertos… She offers an extraordinary, completely unexpected auditory delight. On a period instrument (ca. 1815) the pieces sound more virile and more decisive… The melodies lose barely any of their sensuality and gain so much clarity and warmth.

– Weltwoche, Zurich.

In the press

The wonders of Schubert! …and how well Trudelies Leonhardt serves him up! The playing is sober, but expressive without excessive sentimentality. Everything is there, the sharp accents of a perfectly adjusted fortepiano, the faultlessly clear phrasing, and above all, that subtle fortepiano rubato, its particular mode of expression…

– Diapason, Paris

In the press

What a performance! Such grandeur! An utter delight! These albums were nothing short of a revelation for me… In my eyes, they herald a new era in fortepiano playing.

– G. v. d. L., Utrecht

In the press

Trudelies Leonhardt is first and foremost a virtuoso of phrasing, granting figures and melodies complete narrative freedom.

– M. T. Stockholm

In the press

I am speechless, Trudelies Leonhardt seems to have a hotline to all the composers having their residence in heaven […] really spiritual performances…

– Clavineum

In the press

It is such masterful music-making. It is a lesson to all of us in phrasing, taste, voicing, rhythm, tempo and letting music breathe.

I haven’t heard these wonderful pieces played better. (Drei Klavierstücke by Schubert).

– Donald Allen

Fortepiano

“Musical works should be played on instruments of their time!”

This instrument was built by Paul McNulty in 1992 in Amsterdam, after a fortepiano built by Anton Walter circa 1795 in Vienna. In the lineage of harpsichord design, it has fine strings under relatively little tension and is made entirely in wood. (Metal bracing and framing appeared only later to meet the expectations of increasingly larger recital rooms and concert halls.) Its hammers are covered in leather, and the range is five octaves (FF to g3). Two knee levers activate the registers:

- on the right, the forte register, in which all dampers are raised

- on the left, the moderator register, in which a strip of felt is inserted between hammers and strings to soften the sound.

When McNulty constructed the instrument, he included a third register:

- the una corda register, in which the keyboard is shifted sideways so that the hammers strike only one string, decreasing the sound level.

It is thanks to Christopher Clarke and his ingenious addition of a lyre under the piano, secured by the two front legs, that the una corda register was truly brought into play by means of a dedicated pedal at the left of the lyre. Two other pedals (at the centre and the right) were coupled to the knee levers, offering a choice of using either knee levers or pedals indifferently. Knee levers had, moreover, generally been abandoned in favour of pedals by the second decade of the 19th century.

The instrument is tuned to the average pitch of the late 18th century in Germany and Austria, around 415 Hz.

Benignus Seidner of Vienna built this instrument circa 1815 to 1820 entirely in wood according to the tradition of the day. The leather-covered hammers contact strings that are already a little thicker than those of 18th century fortepianos. The keyboard range is FF to g4. It has four pedals, from right to left:

- the forte pedal raises the dampers and allows all the strings to freely vibrate, creating a richer sound

- the moderator pedal inserts a strip of felt between the hammers and the strings, which softens the sound considerably

- a pedal activating the bassoon register lowers a batten of wood wrapped in paper over some three octaves of the bass section of the keyboard, producing a nasal effect

- the una corda pedal shifts the keyboard slightly to the right so that the hammers hit only one string instead of the two or three strings composing each note.

This fortepiano has a very beautiful walnut veneer, originally stained dark red to imitate mahogany, considered very stylish and elegant in the day. The stain was removed when the instrument was restored in 1977. The fortepiano received its steel strings and slightly broader pins at the same time.

An older brother of Franz Schubert, Ignaz, who gave him his first piano lessons, owned a Seidner fortepiano that can be seen today in the house where the composer was born – the Schubert Geburtshaus, now part of the Vienna Museum. How thrilling to imagine Franz Schubert himself playing on an instrument made by Benignus Seidner!

The instrument is tuned to the pitch of the early 19th century in Austria, around 420 Hz.